Text and Context: Can we understand the Bible?

Have you ever had an argument about the meaning of a biblical text, and the other person complained, “You’re taking it out of context.” What does that mean? Does it really make that much of a difference?

Have you ever had an argument about the meaning of a biblical text, and the other person complained, “You’re taking it out of context.” What does that mean? Does it really make that much of a difference?Context defined

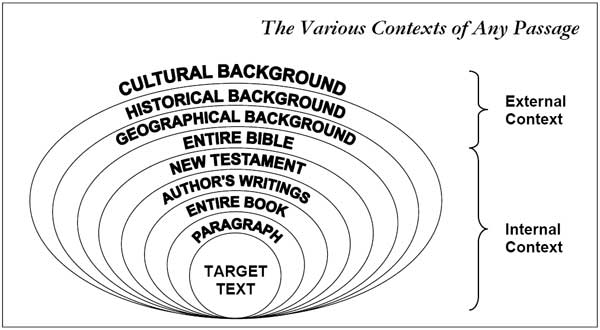

It is true: the meaning of a biblical passage is largely determined by its context, which we usually understand to be the words, clauses, and sentences surrounding the “target text.” A better way to think of it, however, is as a series of rings that surround the “target text” and become ever wider as they move away from it.

Internal and external contexts

Context consists of internal context, internal to the Bible, which includes the paragraph in which the target text occurs, then the section of the book it is in, then the entire book, the other writings of the same author, the entire testament, and the other testament. But context also consists of an external context, which includes the geographical, historical, and cultural circumstances at the time the text was composed.

The more you know about each of these rings, the easier it will be for you to interpret the “target text” correctly. Of course, by “correctly,” I mean the way the author intended it to be understood.

Example: Jesus the warrior?

Here’s a brief example. In Matthew 10:34, Jesus says, “Do not suppose I have come to bring peace to the earth. I did not come to bring peace, but a sword.” Does this mean that He intends to raise an army of warriors and start a political revolution? The context is against that

interpretation. In the immediate context, we find him saying that the decision of whether or not to follow Him will divide families, and those who choose to become His disciples must take up a cross (Matt. 10:35-39), not a sword.

interpretation. In the immediate context, we find him saying that the decision of whether or not to follow Him will divide families, and those who choose to become His disciples must take up a cross (Matt. 10:35-39), not a sword. Parallel passage illuminates

As we go farther away, in Matt. 26:51-56, we find Jesus rebuking a disciple for using a sword to try to prevent Him from being arrested. Jesus tells the man to put away his sword, warning, “All who draw the sword will die by the sword.” He then asks the mob, “Am I leading a rebellion, that you have come out with swords and clubs to capture me?” The obvious answer is no.

Evidence from the Semon on the Mount

At about the same distance from the target text is the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5 through 7). In chapter 5, Jesus tells his disciples to love their enemies, do good to those who abuse them, and pray for those who misuse them. Specifically he speaks of going two miles with one who forces them to go one, which the historical background informs us was just what the Roman occupying force was doing in Palestine.

No armed resistance in the Garden

Going out a little further, we encounter the passage in Luke that is parallel to the target text--Luke 12:51: “Do you think I came to bring peace on earth? No, I tell you, but division.” We know this is a true parallel passage because Jesus goes on to talk once more about division within a family (verses 52-53). When you put the saying in Matthew side by side with the one in Luke, you will see that instead of ‘sword,’ Luke has ‘division.’ In other words, in Matthew’s version, Jesus uses ‘sword’ as a metaphor with the meaning of “division.” Luke just has the literal meaning without the metaphor. You can understand why he might have wanted to avoid the confusion.

Range of meanings with degrees of probability

The more we explore the context, and the more every piece of evidence points in the same direction, the more confident we can be about our interpretation. Of course, sometimes a passage is more ambiguous than Matt. 10:34, forcing us to investigate both the internal and the external contexts long and hard. In such cases, we may lay out a range of meanings and assign to each a degree of probability relative to its alternatives. Many or all of the rules of interpretation might come into play before we can make a confident decision.

Deciding not to decide

Rarely, the probabilities are fairly even, driving us to say with a shrug, “At this point, with the level of spiritual maturity that I have and knowing what I know, I can’t decide which interpretation is correct.” But even this unsatisfying result is better than saying it doesn’t matter or they are all equally valid. It matters, and perhaps later on, when you return to a passage with more information and more experience as an interpreter, the meaning will become clear.

Consult a commentary?

In the mean time, you might take a look at a good biblical commentary, which will lay out the options and walk you through the reasoning process of making a good choice among them. As a spiritual exercise, however, it is best to start with your own analysis, rather than running to a commentary whenever you want to understand a passage. Over-dependence on commentaries stunts your growth as a thinking believer and exposes you to the danger of swallowing everything a commentary feeds you, even if it is wrong.

If you do your own thinking first, then you can dialogue with the commentary, finding either confirmation or correction of your own conclusions, or else telling yourself that the arguments the commentary is making are bogus for reasons x, y, and z.

--Steve Singleton

http://deeperstudy.com

Want to go deeper?

The area of hermeneutics (the art and science of interpretation according to established principles) is the subject of a great deal of scholarly work right now, and hot controversies rage regarding which principles are legitimate and which are not.

Recommended for purchase:

Can We Solve the 666 Puzzle? Using Interpretation Principles to Illuminate One of the Darkest Verses of the Bible by Steve Singleton.  Read excerpt. This is an example of how I apply hermeneutics to interpret a difficult passage.

Read excerpt. This is an example of how I apply hermeneutics to interpret a difficult passage.

Walter C. Kaiser, Jr., and Moisés Silva An Introduction to Biblical Hermeneutics (1993) Read excerpt.

Grant Osborne. The Hermeneutical Spiral: A Comprehensive Introduction to Biblical Interpretation (2nd ed., 2006) Read "Context" chapter.

Online Resources:

Beau Abernathy. "Principles of Interpretation" (2005?)

Frederic W. Farrar History of Interpretation (1886)

Pastrick Fairbairn. Hermeneutical Manual: Intro. to Exegetical Study of NT (1859)

Labels: biblical hermeneutics, biblical interpretation, context

» Post a Comment